A century on, the debate over the Treaty of Lausanne shows no sign of resolution. Jonathan Conlin and Ozan Ozavci explore why it remains such a hot topic.

Jon and Ozan are co-founders of the Lausanne Project.

The First World War did not end in 1918. Fighting continued in the Middle East at least until 1922, when the Greco-Turkish war in Asia Minor ended in Turkish victory. After nine months of haggling in the Swiss resort of Lausanne, a peace treaty was signed on 24 July 1923. Far from a diktat, the Treaty of Lausanne was negotiated between the victors of 1914-1918 (the Allied Powers), and the victor of 1920-1922, a new state we know as Turkey. It was very different from the Treaty of Versailles.

Lausanne was a historical pivot. It sealed the fate of the once-mighty Ottoman Empire, which shattered into a patchwork of ethnic groups jostling for self-determination. The treaty forcibly relocated over one million people, in the name of peace. But Lausanne also sealed the fate of once-mighty British statesman and diplomatist George Nathaniel Curzon, and the arrogant “Old Diplomacy” which he embodied. It marked the birth of the Republic of Turkey, as well as advent of two new players in Middle East politics: the United States and Big Oil. A century on, “Lausanne” remains a shibboleth: for Turks, Greeks, Armenians and Kurds, the name of a Swiss town immediately summons up the hopes and fears, syndromes and conspiracy theories that have shaped the region, and will decide its future.

“Lausanne” remains a shibboleth: for Turks, Greeks, Armenians and Kurds, the name of a Swiss town immediately summons up the hopes and fears, syndromes and conspiracy theories that have shaped the region, and will decide its future.

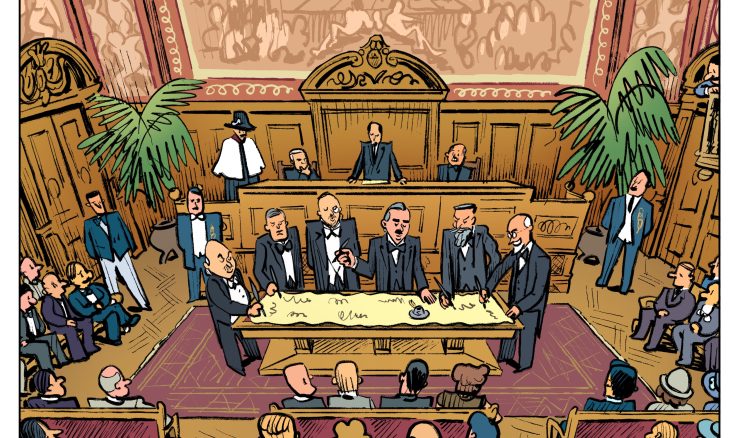

Though Curzon probably did not see things that way, at Lausanne a century ago he was far from having this international stage to himself. One month after seizing power in Italy, Benito Mussolini made his diplomatic debut. So did the Soviets, having just defeated the White Russians (and their western Allies) in the Russian Civil War. One of the first woman diplomats in history, Nadezhda Stanchova arrived hoping to secure Bulgaria an outlet on the Aegean Sea. As she put it in her diary, “If they opened my heart, they would find the name Dedeagatch”, or Alexandroupoli, as the Greek port is known today. Greece was represented by the darling of the Western powers, Eleftherios Venizelos, Turkey by a general-turned-diplomat, İsmet Pasha.

A young reporter named Ernest Hemingway was also in Lausanne to report for the Toronto Star. In between filing stories and bob-sledding he found time to write a poem made up of snatches of newspaper copy and gossip. ‘They All Made Peace – What is Peace?’ gave a fly-on-the-Press-Bar-wall perspective on the squalid horse-trading of diplomacy in the age of mass media.

We returned to that basic question “What is peace?” in the book we produced to mark the centenary of Lausanne, which will be celebrated today. What did peace mean in July 1923? Punishing those guilty of genocide against Armenians and other groups? Dividing up the inheritance of the “Sick Man of Europe”, as the Ottoman Empire had been known, as well as its debt? Or was peace about fashioning a new world order, using new tools such as the “unmixing” of populations” and the League of Nations to sort the former subjects of the Sultan into homogenous sovereign states, states able to take their place in a capitalist global order? To quote Martin Luther King Jr., was peace merely the “absence of tension” or the “presence of justice”?

What did peace mean in July 1923? Punishing those guilty of genocide against Armenians and other groups? Dividing up the inheritance of the Ottoman Empire, as well as its debt? Or was peace about fashioning a new world order, using new tools such as the “unmixing” of populations?

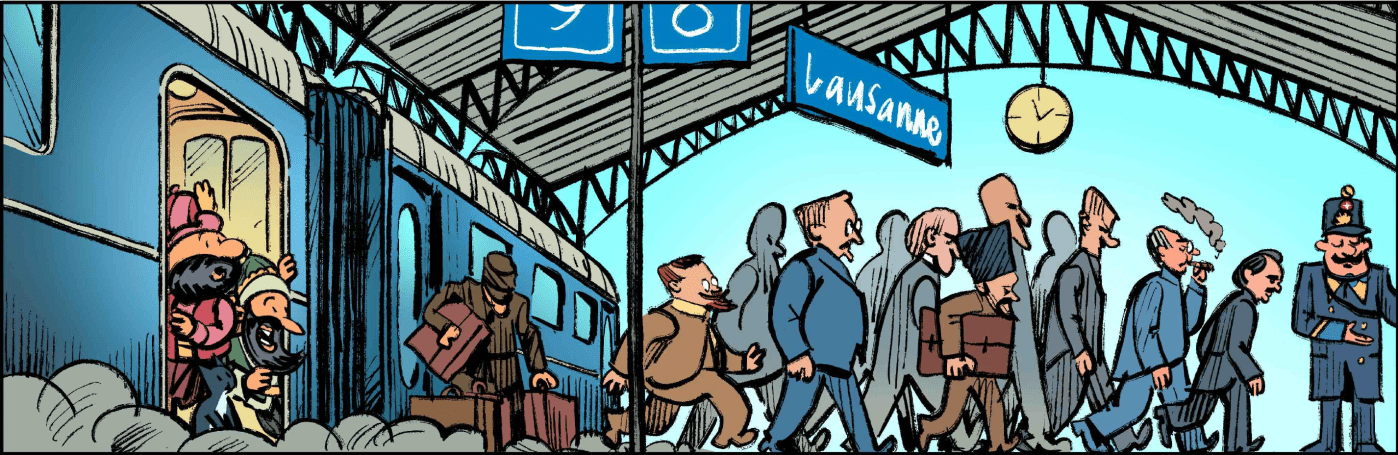

Britain, Turkey, France and Greece had different answers to these questions, as did the many unofficial delegations which flocked to Lausanne (Syrians, Indians, Egyptians, Persians…) eager to exert whatever influence they could gain by lobbying the official delegations, by feeding the media or simply by having exiles, students or other expat communities organize demonstrations. Last weekend has seen those demonstrations repeated, as Kurds and others held clashing protests outside the Palais de Rumine, where the treaty was signed almost exactly a century ago. Meanwhile, down by the lake, the Turkish ambassador will hold a rather more select party at the Beau Rivage, the lavish hotel where Curzon stayed.

Lausanne was the last attempt at peace, replacing the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres: the Ottoman equivalent of Versailles, Saint-Germain, Neuilly and the other treaties which would sow the seeds of renewed conflict. Like them, it included humiliating clauses: Sèvres robbed the Ottoman Empire of the capital it had conquered back in 1453, placing Istanbul and the Straits under “international” control, that is, under Allied occupation. As for İzmir (Smyrna), that second city of the Empire and its hinterland was given to Greece, along with Thrace. Italy got its piece of the pie further south, in Adalia and Rhodes. France got Cilicia in southeast Anatolia. The Armenians received territory to the east, and the Kurds were promised their own nation-state. League of Nations mandates provided a token fig leaf for British control of Iraq, Palestine and Jordan, and for the French presence in Syria. The Ottoman Empire was reduced to a rump state, without access to the Aegean or Mediterranean, its armed forces limited to 50,000 men.

With the not-so-tacit encouragement of British premier David Lloyd George, the Greeks landed their forces in Izmir in May 1919, even though the treaty of Sèvres had yet to be signed. Over the following two years two rival visions engaged in a bloody struggle, which destroyed swathes of western Anatolia, triggering mass migration and unspeakable acts of violence against non-combatants. The “Megali Idea” of a Greater Greece on one side, the “Misâk-ı Milli” or Turkish National Pact on the other. Neither vision could be contained within the terms of the Sèvres settlement. Meanwhile, Greeks and Turks alike were internally divided, between Venizelists and Monarchists on the one hand, and on the other the rival Turkish governments of Istanbul (under Sultan Vahdettin) and, far inland, Ankara (led by Mustafa Kemal, later dubbed Atatürk, or “father of the Turks”).

The victory of Turkish forces against the Greeks in September 1922 made it clear that a new settlement was needed. British foreign secretary Curzon invited both the Istanbul and Ankara governments to Lausanne, hoping to make use of the schism. But on 1 November 1922, the Istanbul sultanate was abolished by the Ankara government. Now Mustafa Kemal alone spoke for Turkey.

A thirty-eight-year-old army officer, İsmet Pasha had been leading the Turks’ “independence war” as commander of the Western Anatolian Army only sixty days before his arrival in Lausanne in November 1922. The transition from making war to peace-making did not come easy. “It was the first time in my life that I took off my boots and put on civilian shoes,” he noted. Bar a short visit to Germany and France in June 1914, he had not been to Europe before. İsmet Pasha is not at all à la hauteur of his task,” one British diplomat crowed, “In fact there is not a single big, experienced and capable man in the Turkish delegation.” Lausanne was expected to be a cakewalk, as well as a masterclass in which Curzon would teach the Americans how “orientals” were to be handled.

İsmet would have to learn on the job. He arrived in Lausanne with a fourteen-point set of instructions from Ankara. These set out the Turks’ redlines: an “Armenian national home”, the capitulations (legal and economic privileges accorded to foreign subjects), limitations on the Turkish army and navy, and the regime of the foreigners in Turkey. All were considered breaches of the sovereignty of the new Turkey. İsmet was under orders to return home if any of these were put on the table. On other issues such as borders in Thrace and Syria, the Ottoman debt and the Straits, he was to seek further instructions from Ankara.

From a Turkish perspective, Lausanne was a response to a deep-seated “syndrome” or victimisation complex, the origins of which date back to the Napoleonic Wars, and which remains dominant in contemporary Turkey. They provide the premise for popular historical soap-operas such as Ertuğrul and Pâyitaht. Thanks to the close ties between the regime and Turkish State Television, these historical dramas and contemporary political dramas exist in a feedback loop: Erdoğan’s supporters cosplay as characters from these shows, whose plots translate the regime’s worldview into the past.

Since the 1990s, the disappointments related to Lausanne have become so dominant among the conservative circles in Turkey that Lausanne, once viewed as a Kemalist triumph (and the humiliation of Curzon), has been radically reimagined, as a Turkish defeat supposedly masterminded by Curzon and Chaim Nahum, the Ottoman chief rabbi. It has not been easy: the only way to make such a counter-factual stick has been to invent fictional “secret clauses” to the Lausanne treaty, clauses which will, so the conspiracy runs, expire today, on the exact centenary of the treaty of Lausanne.

It has not been easy: the only way to make such a counter-factual stick has been to invent fictional “secret clauses” to the Lausanne treaty, clauses which will, so the conspiracy runs, expire today, on the exact centenary of the treaty of Lausanne.

To be fair, for more than a century prior to Lausanne, the question of how to deal with the relative weakness of the Ottoman Empire, better known as the “Eastern Question”, had provided a justification for a cycle of foreign (western) armed interventions in the Empire. These interventions established semi-autonomous regions within the Sultan’s realms. Some of the territories were later annexed by one or other of the European Great Powers, or conquered by surrogates of the Great Powers in proxy wars.

As the surplus capital that had built up within France and Britain sought higher rates of return than were available at home, the Ottoman Empire gorged on loans provided by Western banks, as well as inward investment, including that ultimate “railroad to nowhere”, the German Bagdadbahn linking Berlin and Baghdad. When repayments stalled and the railroads ran out of road, western (in particular French) bondholders who had put their savings in Turkish bonds looked to their own governments to “bail them in,” by means of gunboat diplomacy: hence the British seizure of Egypt (formerly part of the Ottoman Empire) in 1882. Today we are viewing a similar process of financial colonisation take place in Africa, as equally imprudent and large flows of Chinese capital provide footholds for the chipping away of sovereignty – a slippery slope which ends with new Chinese naval bases and the pillaging of natural resources.

Yet this is only one side of the story. On the other side was a tragic litany of mass violence and ethnic cleansing of non-Muslim populations in Ottoman territories. Like all other empires the Ottoman one was a system of inclusion, exclusion, hierarchy and violence. Extreme violence, in some cases; what would later be dubbed genocide. The non-Muslim populations’ liberal nationalist aspirations, as well as associated appeals to the sympathy and support of Western Powers, had long been regarded by the Ottoman imperial, and later by Turkish nationalist elites, as a case of disloyal subjects turning fifth columnists.

An Armenian delegation led by Gabriel Nouradounghian and Avedis Aharonian was also present at Lausanne. With the support of American Christian NGOs they appealed for an Armenian National Home, a semi-autonomous reservation somewhere in eastern Anatolia. As Armenian delegate Krikor Sinapian put it to İsmet: “Even a dog, after you’ve beaten him ten times over, goes back to his kennel. We want to go back to those lands on which we have lived for three thousand years.” A century on, the metaphor and the analogy are equally chilling: how could survivors conceive of returning to live among the people who had sought to liquidate their people? For the Turkish delegation an Armenian Home in Anatolia was out of question. İsmet and the Turkish media knew enough of the Ku Klux Klan to point to the hypocrisy behind American claims to the moral high ground. Would the United States government be willing to consider a plan to “set aside Mississippi and Georgia as a national home for the Negro,” İsmet wondered?

For missionaries like Basil Mathews, Armenians and Greeks were first and foremost fellow Christians. Kemal’s “New Turkey” was a case of “Young Islam” on the march. This was a case of Panchristianism versus Panislamism, a “clash of civilisations”.

The two American delegates at Lausanne, Richard Washburn Child and Joseph Grew, were caught between the humanitarian demands of American missionary groups and the economic demands of American oil companies for access to Middle East oil. For the missionaries, Armenians and Greeks were first and foremost fellow Christians. Kemal’s “New Turkey” was a case of “Young Islam” on the march. This was a case of Panchristianism versus Panislamism, a “clash of civilisations”.

For the executives of Standard Oil of New Jersey (now known as ExxonMobil), by contrast, this was not a “clash of civilisation”, but an “oil war,” in which American oil companies were fighting to defend themselves against “the British oil octopus,” in particular the Anglo-Dutch oil company Shell. Standard Oil were eager to make nice with Turkey, in order to exploit the oil reserves of Mosul in northern Iraq – territory which the Turks claimed “belonged” to their own National Home. American oil companies lobbied the State Department, claiming that Shell was secretly owned by the British government.

At Lausanne, Child and Grew quietly abandoned the Armenian cause in favour of Standard Oil: they encouraged İsmet to defy any attempt by Curzon to revive pre-war oil rights granted by the old regime to the Turkish Petroleum Company (jointly owned BP and Shell). For İsmet the American thirst for Middle East oil provided leverage in his own attempt to claim Mosul for Turkey. In the end, the American delegation agreed to stay away from the Armenian cause, but got into bed with BP and Shell: American oil companies would join Turkish Petroleum Company – the very joint-venture Standard Oil had lambasted a few months. This cast a long shadow over Middle East oil politics. Once inside Turkish Petroleum Company, Jersey Standard used it to delay the development of the Middle East’s oil reserves, in order to keep oil prices high.

For the signatories at Lausanne, “peace” meant amnesty: there was no more talk of holding the Turks to account for the 1915-6 Armenian Genocide. “Making peace” meant forgetting “self-determination” and other promises contained in Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points of 1918. As Elizabeth Thompson has shown, Syrians and other Arab groups had taken the US President at his word, and came to Lausanne hoping to assert their claims to govern themselves – rather than be handed over to France or Britain through a League of Nations mandate. The dreams of Shakib Arslan and others for a sovereign Arab nation-state would be disappointed yet again, with consequences (a gradual turn from Arab Nationalism to Islamism) we are still wrestling with today.

This was as much a Turkish betrayal, in so far as these Arab communities looked to İsmet to defend their interests. Despite his declaration of support for the independence of the Hedjaz (today’s Saudi Arabia), Syria, Palestine and Iraq, made on 4 February 1923, the Arabs were dropped from the agenda once the second phase of the Lausanne talks commenced on 23 April 1923. Syria, Iraq, Jordan and Palestine remained under British and French mandates. For the Syrians, Palestinians and Egyptians, Lausanne spelt the end of their hopes of national self-determination. A year later, Mustafa Kemal’s abolition of the caliphate was a further humiliation.

Meanwhile, the Kurdish case was undermined from within, thanks to competing groups: Pirinççizade Fevzi Bey and Zülfüzade Zülfü Bey took the Turkish side, while Şerif Pașa sought greater autonomy. Whereas Curzon claimed that the Kurds were of Persian origin, İsmet claimed that Kurds were Turks. Unable to conceive that Kurds might be acting for themselves, both the Turks and the British assumed the 1925 Sheikh Said rebellion was a plot by the other.

Finally, Lausanne’s “unmixing” of populations in the name of peace saw nearly one million Greeks living in Turkey, and half a million Muslims living in Greece forcefully uprooted from their homes. Not only had Lausanne failed to address the Armenian Genocide, it made ethnic cleansing into a peace-making tool: one that Zionists now proposed as a possible solution to what they called the “Palestinian Problem”. The exchangees themselves were far from welcome in their new “home”. In Greece their new neighbours called them “Turkish Spawn.” As Curzon predicted, a century on this “vicious solution” has been recognized for the evil it was, a dangerous precedent that would be invoked during the partition of India in the 1940s. And yet population exchanges continue to be seen, by some at least, as a peace-making “solution”; most recently in 2011, during the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue over Kosovo.

What will Erdoğan’s millions of supporters do when they wake up today and find that, rather than expiring in a bonfire of western-imposed borders and restrictions on oil production, the treaty remains in force? Are Turkey and Greece ready, as open-minded commentators hope, to recognize the events of a century ago as a shared trauma of imperial collapse, and work within the Lausanne framework to settle recent disputes over the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean islands? Does Lausanne have what it takes to last another century?